|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jay Holben, Director of Photography

|

|

|

|

Jay Holben

Director of Photography

Jay Holben has been a full-time director

of photography for the past six years. Previous to that his work as a chief lighting technician included future films such

as Free Enterprise and music videos for artists such as Brandy and Monica, Monster Magnet and Ice Cube. As a cinematographer,

his work encompasses micro and low-budget feature films, commercials, music videos and a bevy of short feature projects. Although

his primary tool of choice is 35mm motion picture emulsion, Holben has served as a director of photography for three 24p HD

projects (including two long-form interactive commercials for General Motors) in addition to directing his own 24p HD short.

Holben has also photographed more than two-dozen DV projects within the last two years. Some of his DV work has included extensive

Multicam conceptual tests for Steven Spielbergs Minority Report and digital effects element photography for this years

Dreamworks, SKG holiday release, Surviving Christmas.

Additionally, Holben is a frequent contributing

writer for American Cinematographer magazine and The Hollywood Reporter.

He has authored nearly 100 articles on cinematography and the technology of the art.

IMDb Filmography

|

| Still shot from the film "Paranoid" |

Answer This?

Q & A with Mr. Holben

Film Addiction: I noticed on your reel that you tend to frame

a lot of your characters offset to the side. Is this a personal style of yours or do you let the scene dictate that?

Jay Holben: My

compositional style often falls to placing subjects in the extreme of the frames. I'm a big fan of the 2.40:1 aspect ratio

and love to play the extremes of the image for dramatic effect. However, this - like everything else - must be motivated by

the script, the scene, the actor's subtext and the director's subtext. Each narrative moment requires a different compositional

interpretation. Although I've had a number of discussions on composition and framing with many cinematographers, I find

them difficult and challenging to hold. Composition is such a subjective thing, but it's really about directing the audiences

eye to a specific portion of the frame where the storytelling is happening. That's really the art of framing. I worked on

a short film called Waiting for Ronald, directed by Ellen Gerstein. It was her first film behind the camera and on the second

day she came to me in a panic. Apparently the script supervisor had questioned Ellen about my compositional choices and Ellen

was distraught. She came to me and asked me if I was making a mistake by cutting off the tops of everyone's heads in these

shots. I smiled and said, no, that's a deliberate choice. It's actually a technique that I stole from Conrad Hall. Since the

sequences we were shooting were very intimate, it was really all about the actor's internalization of his stress at the moment.

By placing the eyes higher, toward the top of the frame, it created a more intimate composition to make the emotion in the

actor's eyes more important and emulate a more empathetic response from the viewing audience. She accepted my response, reluctantly,

and we continued shooting. Later, in editing, she thanked me for "sticking to my guns" there and said she completely understood

what I was doing when the picture was cut together and that sequence came to play. Each situation, and indeed each director,

creates a different mandate for framing. That's all the long answer to the question. The short answer is that I love

to play the extremes of the frames, especially in moments of tension. There are frames in a project that I just directed where

I asked Christopher Probst, my cinematographer, to hold only one of the actor's eyes in the very far right of the 2.4:1 frame

and emptiness in the rest of the frame. It creates a wonderful feeling of tension. Along those same lines, I do find it very

difficult to compose in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio. Working in such a tight box is very difficult for me and I am often not happy

with my compositions there.

FA: What equipment (camera,lenses, etc.) do your prefer to work with?

JH: I'm

really a Panavision guy through-and-through. From early on in my career, Panavision has been extraordinarily supportive and

philanthropic toward me. Additionally, their equipment is absolutely top of the line and their service is unparalleled. On

many projects, I request a Panavision package and I'm usually met with "Oh, I don't think we can afford that..." but on further

investigation most producers find that Panavision is extremely cooperative and competitive with any other company of merit.

They are always my first choice. Specifically, from there, I usually work with the Panavision Platinum or Gold II cameras

and, as often as I can, the Primo series of lenses - although that depends on the specific project. I have yet to find a series

of Panavision lenses that I am not happy with from the Zeiss Standard Speeds to the Ultra Speeds to the Primos - I think they're

all fantastic pieces of glass. When it comes to high-definition, I again turn to Panavision for their Sony CineAlta F900 cameras

with Digital Primo lenses. I have worked with the F900 before from another company without Panavision's retrofit and it's

nowhere near as nice to work with. When it comes to grip and electric equipment, Illumination Dynamics has always come through

for me - especially in times of extreme need. Their support and staff are fantastic and they're always the first call I make.

If I'm forced away from Panavision, I'm really kind of ambivalent about other gear - Arriflex or Moviecam are both good packages,

but I never feel as comfortable with them, especially if I'm operating.

FA:Tell me a bit about your teaching background. What type of training do you

offer? Where are some of your formal pupils now?(Just to let you know that I am a high school teacher as well, so I was intrigued

by your teaching background)

JH: Teaching

was really a fluke. I was extremely involved with my high school theater program, especially the behind-the-scenes aspects.

I spent my time learning the technical art of theater and by the time I was a junior, I was working outside the school professionally

in addition to running all the technical aspects of the performing arts program. When I graduated, the drama teacher made

the comment that it was a shame that none of the younger students knew how to run the theater the way I did. I suggested that

I might create a program to teach them how to run the theater and she said that was a wonderful idea. That summer I worked

on a plan and proposition and returned to the school the following year with my program lined out on paper. It was accepted

with flying colors and I was hired into an addendum position as the facility technical director and an addendum instructor.

Taking a cue from the professional technicians that I was working with, I taught an extremely intensive, mainly extracurricular,

program to the most dedicated students. Instead of just teaching which rope to pull to make a baton drop toward stage, I taught

the students the physics and inner workings of each component of the theater. We learned not just the hardware names, but

how they were made, why they were used, how they related to the overall system and what laws and codes governed their usage.

To pass my course you needed to understand the hows and whys of everything behind the scenes in five major areas, each

building on the other: Stage Hand, Rigging, Sound, Lighting and Stage Management. The students were then "certified" in each

department and ran all the technical aspects of events within the facility. The first year, I learned right

along with the students. I worked from my existing experience, but would then read the "homework" right with the assignments

and come back and work with the students on the new material. We learned together. At one point, in my second year in

the program, I was comparing notes with a friend who was in the technical direction program at USC and we were covering material

in our first two weeks of the lighting section that he was just starting to cover in his junior year at SC. In the three years

that I was teaching the program, it became widely recognized throughout the professional theater community in Arizona and

my students were welcomed into the working world with open arms. The poster-child for the program was Mark Reynolds, who came

to me as a baseball player and left as a qualified Stage Manager. Just after high school Mark landed his first high-profile

position as stage manager of the national Broadway tour of Smokey Joe's Cafe and followed that up with a three year stint

with Walt Disney Special Events touring the country, once again, with live shows. In addition to my work with Horizon High

School, every couple of years I am invited to teach a workshop or seminar on the art and technique of film production. The

largest of these was a 48 hour seminar in Arizona (spread out over four 12-hour days on two weekends) on the work of the motion

picture electrician and lighting for film. Most recently I gave a four-hour lecture, hosted by the American Society of Cinematographers,

American Cinematographer Magazine and Panavision, on the basics of motion picture cinematography to a number of industry-related

journalists. I love the experience of teaching, and love the opportunity to talk about the business and share whatever knowledge

I can. I have also served as a mentor for half a dozen young cinematographers, most who originally contacted me through the

Internet.

|

| Still shot from the film "Paranoid" |

FA: What drives you to do better

or improve on each shoot?(or have you developed a style and are happy with the status quo).

JH:I'm never happy with the status quo. I'm always

looking for ways to improve and ways to better tell the story. It's one reason that I'm not a fan of storyboards. Unless you're

talking about a complicated special effects or action sequence, storyboards tend to constrain people into a singular

idea without allowing the organic nature of the moment on set to inspire the shot. I prefer to watch the actor's blocking,

look at the set and rough lighting and get an idea of where best to cover the scene at hand. I've had many conversations about

"closing the deal" on each shot, each moment; optimizing the moment to be the best that it can be. However, all that

having been said, I am also extremely conscious of schedule and time. I am, more often than not, willing to compromise the

'perfection' of a shot for the greater whole. I believe wholeheartedly that a movie is greater than the sum of its parts.

One simple or boring shot isn't going to ruin a movie. And, at the same time, I am never looking to shoot a shot

just for the sake of shooting a shot, or making a shot 'cool' just for the sake of being cool. Everything must originate from

the story and the dramatic impact of the moment. I am not a fan of all flash and no substance. I much prefer all substance

and no flash. So there's a bit of a dichotomy there. Although it isn't necessarily easy for me, there are many times

in the past when, for logistical reasons whether that be schedule or other constraints, that I have merely shot what I could

shoot to get the footage "in the can" and move on. On the show I mentioned earlier, Waiting for Ronald, our first day of shooting

the camera and grip and electric truck was six hours late arriving to set. When it did arrive, it came with less than half

of the equipment I was expecting. Having already lost six hours of shooting time, I completely altered my original shooting

plan and photographed an entire sequence purely in natural daylight to try and make up time on the schedule. It's not the

most perfect approach - but in that situation, it was the only choice to get the film made and keep us on schedule.

FA: What would be your dream

film job? or who would you like to work with that you have not had the opportunity to work with yet? Stretch yourself

hear, because some peoples usual response is :waking up and doing what I do everyday.

JH:Well - my answer would have been to be able

to continue to work successfully at making movies, but you've asked me to dig a little deeper so here goes: I would very much

like to be in a position of running my own mini-studio. If you look at where Steven Spielberg is today, that's my dream job.

To be able to have my pick of productions, yet be able to be the enabler for many other productions that I'm not necessarily

helming. To turn Adakin Productions into a company that makes five to ten features a year would make me very happy, indeed.

FA: Do you see the death of film on the horizon? Do

you think you will ever switch over to video as a permanent media?

JH:This is a very difficult question - and there

aren't any simple answers. I do not have a crystal ball and I'll never pretend that I can tell the future. In my opinion,

digital acquisition media will eventually replace motion picture emulsion for the capturing of moving images. Right now, 24p

High-Definition video is VERY close to being able to do that, and that technology is only going to continue to improve. Eventually

we will see motion picture film only shot for huge event movies, much like 70mm film has been used in the last twenty

years. Digital technology has already proliferated the post-production process and it is a very welcome proliferation indeed.

The power of the digital tools now available to the filmmaker in post are extraordinary and, once again, they're only going

to get better. However, that is one of digital's downfalls: the constant evolution and therefore obsolescence of outdated

technology. As we move from one compression standard to a next (please give us a standard soon!) and one tape format to the

next and one acquisition format to the next - each inferior format becomes obsolete. When it comes to archiving and saving

the materials generated in these mediums, it becomes an overwhelmingly expensive to migrate the existing footage from

one medium to the next - and with digital media there is a tendency to not keep all elements. Additionally, what may be captured

today at 1920 x 1080 resolution, is stuck at that native resolution when transferred later to something at a higher resolution.

Currently motion picture film is the highest image quality of any existing medium (estimated at 6K image resolution - 24p

HD isn't quite 2K yet) and the one with the greatest longevity. It only takes light and the human eye to see an image on a

piece of film whereby if we are to see a DigiBeta tape in 10 years, who is to say there will be players available to

watch the tape? Currently it is easier to see re-runs of I Love Lucy from 1951 (shot three-camera on film) than it is to see

video news footage from 1980. Additionally, as television technology improves from standard definition NTSC to high definition,

those original film elements from 1951 can grow right along with the technology and still outlast it - older video cannot.

Even further, we can see the original Battleship Potemkin from 1925 in all its' grandeur almost eighty years later, but I'm

in trouble if I try to watch a 2" video reel from a television broadcast just twenty years ago. For this reason alone, motion

picture film is still the best medium of choice - if for nothing else than properly archiving elements - and it will continue

to be so for a very long time. Digital technology is definitely here to stay and the next decade will see it infiltrate standard

production to an increasing degree and, perhaps, exhibition as well, but we're not going to see the death of film completely

for a very, very long time.

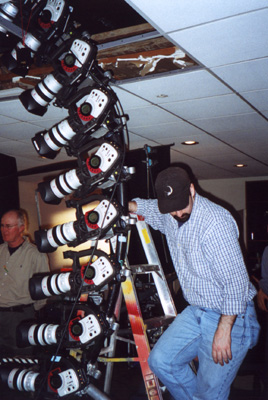

FA:One last question: In one of your pictures

you are shown with a whole bunch of DV Cams on a circular rig. Explain this shot. What film was it used in?

Looks like a very interesting shot.

JH:That was from Minority Report. Early on in

pre-production Steven Spielberg was unsure about how he wanted the pre-cog visions to look and visual effects producer Mark

Russell contacted me to go over some ideas. Mark and I batted around a few concepts and I did some previsualization work for

him on our ideas before we locked down an official concept to test. I was the cinematographer on a day of digital test shoots

to help Steven see a couple different ideas. ILM and Imaginary Forces then took the footage we shot that day and each came

back with their own looks. Imaginary Forces won the job and did all of the pre-cog visions for the film itself.

After quite a bit of discussion, and a previous day of conceptual

test shooting that Mark and I did together with Black Box Digital (another effects company) I sold Mark on the idea of working

with Reel Efx with a "bullet-time" concept - like the freeze frame moments in The Matrix - but doing it with video cameras

instead of still cameras. This way the shot could morph or roll from one camera to the next while it was still in motion and

have a very unique feel. It's a technique that has been done many times since - and was really refined by Jim Gill of Reel

Efx. At the time, it was extremely difficult to get 30 XL-1 cameras, and we wound up with 20 XL-1s and 10 PD-150s. The shot

you see of me there is actually just the 20 XL-1s on a large "C" shaped piece of piping. The shot was of a drug dealer who

was sampling some cocaine over a glass table. While he was sampling, a rival dealer came into the room and shot the snorting

dealer in the back of the head. The idea was to have a shot of the shorting coke and then a shot of blood coming back out

the straw and soaking the coke on the table. It was an idea that Steven wanted to see and was considering for the film. The

camera rig started in the ceiling above the table and swooped down under the glass table to be looking through the glass at

the soon-to-be-dead dealer.

Jim and his Reel Efx crew went out for a day of shooting with

main unit cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, just a couple of days before principal photography started, but Janusz wasn't happy

with the cumbersome rig that it takes to bring out 30 cameras and they nixed the Reel Efx rig for the film.

Some of the footage we shot on this day is seen on the special

edition DVD of Minority Report, but was not used in the actual film. They did not use the multi cam idea at all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|